Appreciating The Forest For The Trees

Courtesy of Philip Hall

Golfdom

When the Gold Course at Golden Horseshoe Golf Club in Williamsburg, Va., opened for play in 1963, Robert Trent Jones Sr. weighed in (as he often did) with a few well-chosen words on the nature of his creation. In time, the Gold would be recognized among the top 100 courses in the United States. But at the unveiling he hailed it as merely “a natural arboretum upon which a great golf course has been built.”

In the spring of 2016, Colonial Williamsburg — the private foundation that administers the sprawling living history museum in addition to the 45-hole Golden Horseshoe resort — pulled the trigger on a long-awaited overhaul to the Gold Course. Other than a course-lengthening project conducted in 1998, it had never been the subject of consequential renovations. As RTJ Sr. passed away in 2000, his son Rees (who had designed the neighboring Green Course in 1991) was engaged to lead the effort.

Seeing the trees for the forest

Industry attitudes toward golf-enabled arboreta have changed a great deal since 1963. Many architects today brag not on how many trees they preserve, but on how many trees they take down. The parkland style hasn’t exactly fallen from favor, but high-profile tree-removal programs at major championship venues like Oakmont (Pa.) Country Club and myriad other classic courses around the country have changed the way many view forested courses today and how they should be renovated, updated and presented going forward.

When the Gold Course reopens June 1, don’t expect an open expanse. But, in the view of Rees Jones, the selective, maintenance-centric nature of the tree-removal process in Williamsburg serves as a riposte to what he sees as a dangerous trend in North American course renovation.

“I think this wholesale clearing of trees is a disaster,” says Jones, who has directed a few U.S. Open preps of his own — seven to be exact. “Yes, many of these original sites were not forested, but Ross and Tillinghast also had tree-planting plans for many of their courses. This course here was built in a forest, and that’s what makes it a great golf course. Somebody has to stop this absolutely insane trend of cutting down all the trees. It just doesn’t make sense everywhere.

“One thing about this course: It was an arboretum. Dad called it that. The trees are very much a part of the routing, the strategy. We thinned out some trees, but it’s still a proper parkland golf course. We probably removed 100 trees, but we did it mainly for the agronomic benefits.”

Tree-removal definitely did not wag the dog on this project. Jones, colleague Greg Muirhead, Golden Horseshoe Superintendent Randy Waldron and a construction team from Landscapes Unlimited removed some 100 trees to benefit turf conditioning. They also oversaw the complete re-grassing of all fairways and rough areas with NorthBridge bermuda. Each putting surface was recontoured (four were completely rebuilt and/or re-sited) before being seeded with 007 bentgrass. Eight new tees were added, while every bunker was reshaped and rebuilt using the Better Billy Bunker system.

Perhaps most noteworthy, they managed all this (with help from a new technique) within the confines of Virginia’s limited growing season.

The NorthBridge difference

Muirhead, Waldron and Landscapes Unlimited Project Manager Dana Grode all sung the praises of NorthBridge, and not merely for the deep green hue it’s been bred to exhibit earlier each spring and hold longer into the fall.

“We settled on NorthBridge to replace what had been common bermuda because it’s much more cold tolerant,” says Waldron, formerly the superintendent at the Golf Club of Georgia. “We had 65 to 70 acres of existing common bermuda here. I sprayed it out three times prior to the contractor even being on site. But we used a new concept here: sod sprigging, or sod-to-sprig. Where they used to take a roll of sod, cut it up and spread it, this new method does less of that cutting — the sod is almost viable when it hits the ground. That was a big upside, because it’s not a big growing window here in Virginia.”

This was the first sod-to-sprig experience for Grode. He came away impressed.

“The application is similar to sprigging, but instead of sprigs being harvested from a turf field and transported to the site as sprigs, what you get on site is actually sod,” Grode says. “We run it through a machine that grinds it up and applies it. The grow-in did really well, good coverage.”

“We were lucky, too,” says Muirhead, “because we avoided some big storms during grow-in,” adding that relatively dry conditions also benefitted Better Billy Bunker installation, where the gravel layer must be relatively dry for the polymers to properly adhere. “We dodged a lot of delays there. That, combined with sod-to-sprig, got this project done on time. But you can’t underestimate the presence of Landscapes Unlimited. They have all the resources you’ll ever need.”

Muirhead is referencing not just the Gold Course, but his firm’s additional renovation work at Piedmont Driving Club in Atlanta, Carolina CC in Raleigh and Atlanta Athletic Club. Rees Jones, Inc. worked alongside Landscapes Unlimited at all four venues in 2016.

Trouble over the decades

Fifty years is a long time between grand opening and meaningful renovation. The specimen trees that comprised the original arboretum at Golden Horseshoe have grown ever more mature, and that’s just fine with Jones and Colonial Williamsburg. By 2014, however, the turf, drainage, green and bunker situations at the Gold Course had become increasingly troublesome. In retaining RTJ’s son to renovate, the foundation hardly could have found a more sympathetic renovator.

By sod sprigging, Waldron was able to grow-in the course in Virginia’s short growing window, saving a month’s time.

“Dad had some nice-looking contours in these bunkers,” Jones says. “Often he and Dick Wilson would have smaller bunkers with a single nose. Later on, those bunkers got bigger and you had multiple noses because the excavators were bigger. They are fairly wide and pronounced here, and they’re going to look phenomenal, in part because they have the right depth to them now. Most of them are pitched uphill, but because they’re Better Billy Bunkers now the ball releases away from the sides, as it should.”

For the record, the Better Billy Bunkers at the Gold Course should function to perfection. Landscapes Unlimited is an authorized installer, and Billy Fuller, the man who invented the system, served on the project as an owner’s rep.

Getting the putting contours right

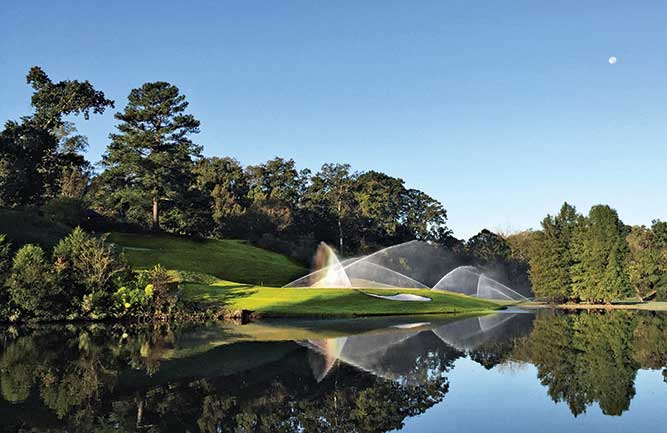

Jones also adjusted the contours on most putting surfaces, and moved No. 18 to the pond, allowing for long views to the lake and clubhouse. Greens were grassed with 007 bent, which replaced a Penncross/Poa annua mix.

Muirhead notes that a major project goal was to maintain and improve playability on what has, for 50 years, been a challenging golf course. Hence the new forward tees, two new drop areas and softer contours on the remaining greens. “We’re increasing playability and giving the client an opportunity during tournament play to keep these putting surfaces a little faster than they could before,” he says.

While the budget for this renovation ($2.5 million) was determined in 2015, evolving situations on the ground served to change the equation somewhat.

“Any time you do a renovation like this you don’t know what you’re going to find,” Waldron says. “You feel comfortable with the scope of things, but then two weeks later you find something you didn’t expect. One of the things I’d like to articulate is the willingness of Robert Underwood (Colonial Williamsburg’s VP of operations) to allow Landscapes and the whole team to bring things to him and say, ‘We uncovered this issue that we didn’t know about.’ To his credit and Colonial Williamsburg’s credit, he allowed Landscapes and us to correct these things.”

Grode agreed: “It turned out really well considering all the moving parts, and that comes down to the people involved. Randy is such a hands-on superintendent. He was there every day interacting with our crews. Billy Fuller offered a lot of really great input, mostly stuff that had nothing to do with bunkers. And Greg Muirhead does such a good job working with everyone involved. I found it admirable how he worked with everyone toward solutions.”

Waldron has been on site since April 2016. That’s when he joined BrightView, the former ValleyCrest Golf Maintenance, which earlier in 2016 partnered with Colonial Williamsburg to handle maintenance for all 45 holes at the Golden Horseshoe. While Waldron’s arrival coincided with the onset of construction last spring, his long-term strategies required little adjustment.

“My attitude toward renovation is to get things in place that will help me not do so many of the routine things that take up valuable time,” Waldron says. “Not shoveling bunkers, for example, means staff is freed up to tackle the detail stuff that really makes a course jump.”

Another example, he says, was chronic drainage issues. “Why not correct those now, while the golf course is closed? Here’s another one: The tree removal we undertook here. There was good bit of it on the front end of this renovation, which means we won’t have to remove them later when we’re open for play. By taking out those trees, which were dead or dying anyway, we’re getting a lot more sun on areas that were struggling. That means less sodding each spring.”

That’s called seeing and appreciating the forest despite the trees, and it represents a removal strategy most anyone can get behind. Even Rees Jones.