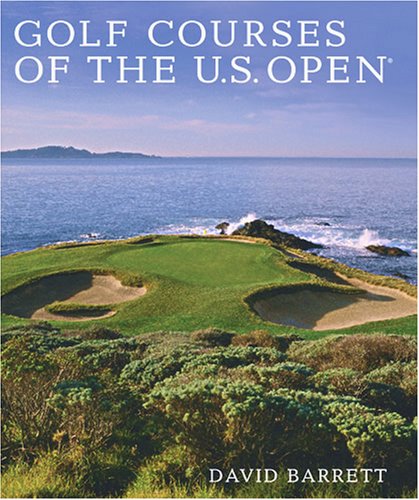

Golf Courses of the U.S. Open, Foreword By Rees Jones

Foreword By Rees Jones

David Barrett’s book, Golf Courses of the U.S. Open, includes a forward by Rees Jones as well as descriptive stories of the 12 Open courses that “The Open Doctor” renovated.

Some of my favorite childhood memories are from the U.S. Open. I went to my first in 1950 when I was 8, and stood right behind Ben Hogan when he accepted the winner’s trophy at Merion Golf Club. In 1955, I remember standing on top of a station wagon (there were no stands) near the 18th green of the Olympic Club to watch Jack Fleck make his putt on the 72nd hole to tie Hogan. (Fleck won the playoff.)

My father, Robert Trent Jones, already was a well-known golf course architect when he began his involvement in remodeling and renovating courses for the U.S. Golf Association’s biggest championship, the U.S. Open. As a result, our family got to travel to almost every championship. In the more than 50 years since, I think I have missed a dozen Opens.

I did more than watch during those childhood visits. During the 1954 Open at Baltusrol Golf Club, I measured the length of the drives hit by the players, which helped Dad to reposition Olympic’s bunkers in preparation for the following year’s Open.

I did not attend the 1951 Open at Oakland Hills Country Club, but I remember the controversy over my father’s redesign. Dad had been hired by the club to bring the course back to its pre-Depression glory and to modernize it for the upcoming championship. Even then, Dad was concerned about the implications of improvements in golf equipment, so he lengthened and toughened the layout.

Some would say he made it too tough. There were only two scores under par. The winner, Hogan, passed my mother in the crowd after his final-round 67. She congratulated him on his score, and he replied, “Mrs. Jones, if your husband had to play his courses for a living, you’d be in the bread line.”

The Oakland Hills Open was a milestone in the history of the championship. It was now evident that the classic courses, venerable though they were, would require at least a little updating against the onslaught of technological advances in the design of balls and clubs. I understood even then that the U.S. Open was the ultimate examination in American golf, and, as such, the host course would have to keep up with the times. Although every golf course at that mid-century point had undergone its share of tweaking, changes for a layout selected for the championship had become a given.

Between 1951 and 1962, I watched closely as my father prepared Oakland Hills, Baltusrol, Olympic, Oak Hill Country Club (’56), Southern Hills Country Club (’58), and Oakmont Country Club (’62) for Opens. After that, the USGA selected two courses with nine holes of his original design–Congressional Country Club’s Blue course (’64) and Atlanta Athletic Club’s Highlands course (’76). The USGA also selected two of his original 18-hole designs, Bellerive Country Club (’65) and Hazeltine National Golf Club (’70).

Since those courses have held Opens, all of them have been renovated to varying degrees. That’s the influence of advancing equipment technology, as well as athlete training and conditioning.

In 1985, I had headed my own golf course architecture firm for 11 years when I got a call from The Country Club. They wanted to restore and modernize their revered old course in Brookline, Massachusetts, in preparation for the 1988 U.S. Open. That was my first Open redesign; I was 46, the same age as my father when he redesigned Oakland Hills.

Between then and now, I’ve had the good fortune to renovate 12 of the 50 courses in this book, continuing the efforts begun by my father to make U.S. Open sites championship-worthy for contemporary players. (And in some cases, my renovations came on top of my father’s own redesign work.)

Five of the 12 were remodeled after being selected to host the Open: The Country Club, Hazeltine National (’91), Baltusrol (’93), Pinehurst Resort & Country Club No. 2 (’99), and Bethpage State Park’s Black course (’02). Two opted to remodel hoping (successfully, it turns out) to attract the tournament: Congressional (’97) and Torrey Pines South (’08). Five courses had previously hosted an Open and some entertained the possibility of attracting a future Open: Atlanta Athletic Club, Bellerive Country Club, Medinah Country Club (No. 3), Oakland Hills Country Club, and Skokie Country Club.

Each experience was another step toward the redesign of the next course. Once, a friend asked me which players I followed during a recent Open. I answered that I wasn’t just watching a player; I was watching the course. The interaction of player and course helps me understand the routing, strategy, and design features that factor into a championship-caliber layout.

While working on the different courses, I researched and read about the original course architects, trying to get inside their heads to understand their styles and strategies, studying why their courses were regarded highly enough to be selected as U.S. Open sites in the first place. I also watched competitions on courses that I came to know quite well.

Every renovation is a different process. I approach each course on its own merits: strengths and weaknesses, flexibility, ability to withstand changes without compromising its character. I delve into the club archives, scrutinize old photos and aerial maps, and track down historic references.

The designers at Rees Jones Inc. never go to a course and simply and automatically add length. We do add yardage to challenge the awesomely long drives today’s pros are capable of hitting. But we also sometimes eliminate a blind hole, reposition fairway bunkers, add greenside bunkers, change the green size (at The Country Club, we enlarged one green and made three smaller), take out trees, add a pond, or change the angle of a tee box.

We redesign so that when the USGA sets up the course, the players believe that the course is a fair test of golf skills. We try to make the player use every club in his bag and penalize a shot only to the degree that it is missed.

And the process is not a singular effort. The host club, the USGA, and the consulting architect become a team. Whatever changes our design firm makes, we first submit to the USGA for approval. This cooperation is crucial. Quite often, the USGA provides input that is implemented in the design.

I remember standing with USGA Executive Director David Fay on the 18th fairway at Bethpage State Park’s Black course during the renovation prior to the 2002 Open. He said, “Let’s add a bunker at this green,” and I immediately saw his point and agreed. Once our remodeling is done, the USGA takes it from there for the championship. It is the USGA, not the architect, that determines the narrowness of the fairway, the height of the rough, the hole locations, the speed of the greens, and other playing characteristics.

In 1954 at Baltusrol, gallery ropes were introduced for the U.S. Open. The primary reason was not to control the gallery; it was to protect the course setup because when the crowd walks and tramples the grass, the rough becomes much less effective as a penalty for players missing the fairway. I remember a big discussion among the club officials and the USGA about how they were going to pay for this new expense. My father even suggested putting advertising on the support posts to raise the money. (That’s probably when, at 12 years of age, I learned the importance of course setup.)

Today, the ropes are being moved even farther away from the centerline of the fairway. Each year, the USGA makes choices in order to present the ultimate–but fair–test given the unique qualities of each course. No more “monsters” in the vein of the 1951 Oakland Hills Open.

David Barrett, by the way, unearths the truth behind the quote–“I am glad to have brought this course, this monster, to its knees”–about that event that has been attributed to Hogan for decades. You can read that story–and my father’s involvement in the plot–in the Oakland Hill chapter.

For decades, David brought readers this kind of insider information as the man responsible for overseeing the major-championship previews for GOLF Magazine. Now, his intimate knowledge of the courses and his insights, coupled with his thorough research, enable him to write skillfully and smoothly about these 50 illustrious courses and their championships–past, present, and upcoming.

In Golf Courses of the U.S. Open, David perfectly integrates the story of the golf course with accounts of the championship, painting a colorful and informative panorama. I wanted to read it slowly to savor every detail, but I was so caught up in the stories, I found I couldn’t turn the pages fast enough. His anecdotes are so lively that I felt as if I were right there in the gallery at Myopia for the 1901 Open, which “set the all-time standard for misery”! As immersed in the game of golf as I am, I was fascinated by golf lore that I had never heard before, especially about a subject that is so close to me.

Besides telling a colorful story, David has a historian’s gift for interesting details that shed light on the early Opens, years when golf professionals were regarded as second-class citizens and golf tournaments were attended by hundreds, not tens of thousands, of spectators. He delves thoroughly into the architectural history of the courses, describing the evolution of their designs over more than a century. In doing this, David also brings the golf course architects to life, especially those giants of “The Golden Age of Architecture” who designed most of the courses that have hosted the Open.

The U.S. Open is an event that occurs only once a year and the title of champion is a coveted one. David gets inside the players’ heads and brings the reader an understanding of the mental challenges in this pressure-packed competition.

Golf Courses of the U.S. Open will be interesting reading for all golfers, who have watched the Open on television or have been lucky enough to attend the event itself, like I have. It is a great contest between the golf course and each golfer. This book will change the way you view the United States Open Championship.